The other day I joined the growing ranks of men who have admitted IKEA into their homes to remodel bedrooms and dismantle masculine self-concepts. Real men hate IKEA, I hear. But I’ve always fallen short at being a real man. It’s not that I don’t fall prey to wanting to be one. It’s not that I don’t understand this hostility to IKEA, particularly their instruction manuals.

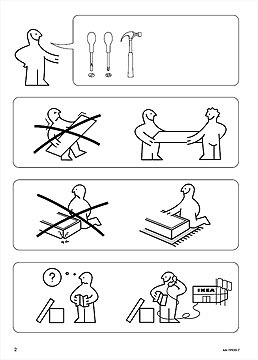

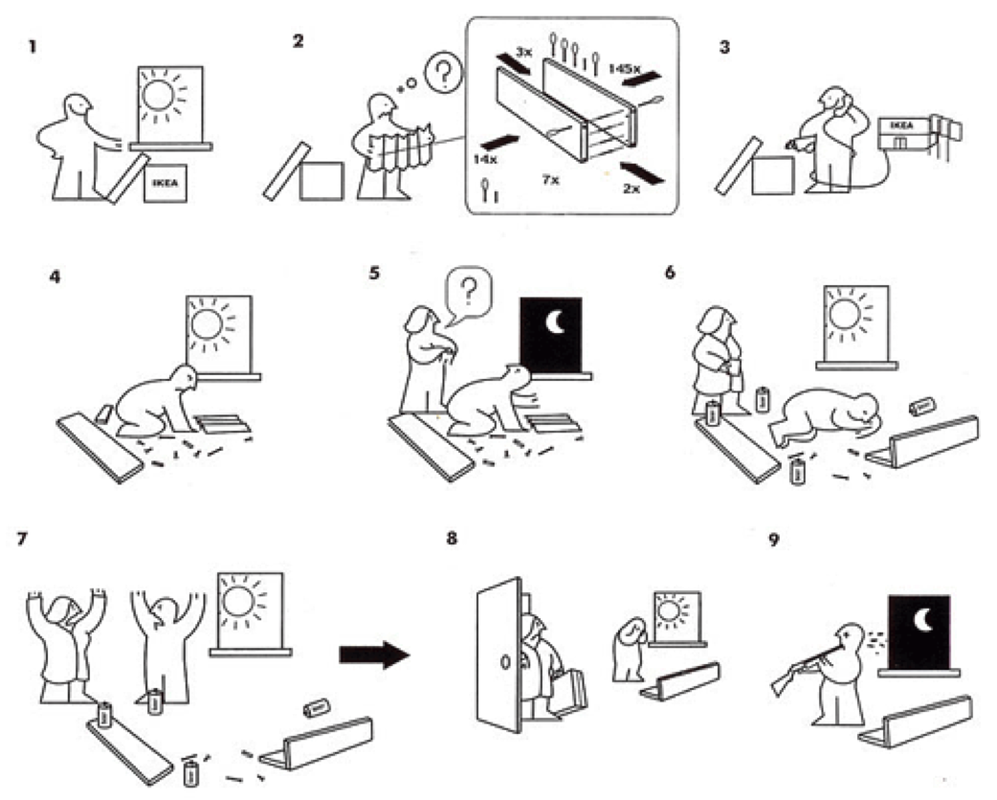

Who exactly do they think they’re speaking to, anyway? That shapeless line-drawn androgynous figure there with pencil in ear and placid helper standing alongside certainly isn’t me! And how dare they draw an oversized X through my manly need to build it alone. (It’s not surprising I assumed the figure bent over and struggling alone was male, while the star-headed helper was his female counterpart.) And how dare they make it near impossible to construct anything more complex than the BILLY bookshelf without following their step-by-step procedures, in order and to the letter. Everyone knows instructions are for losers. Any handyman worth his salt can look at the parts and figure it out instinctively; he’ll finish the job and leave the site with two nuts and a screw to spare, always. Their quasi-opaque pictographs don’t look like me and don’t speak to me: they must be talking to somebody else…

But in fact I did have a female partner to help me, and in fact I did follow the instructions to the letter—because I’ve disobeyed the IKEA imperative before and the botched result made me feel even less manly than the kind of man IKEA would have me be. So it was absolutely necessary to obey the manual step-by-step, as a twosome, lifting together and sorting together, discussing, consulting, agreeing and building—with each of us up in each other’s business. It suddenly struck me that IKEA manuals aren’t instructions at all: they’re relationship and gender maps.

This realization came to me when I decided to deviate from our agreed-upon way of doing things and proceeded to hammer the backboard onto a wardrobe unit. Here I could finally reclaim some trace of manhood through the grip of a 12-pound hammer and a two-penny nail. I was determined to hammer each nail like a samurai, sinking each with a single strike. I’d be damned if I was going to fuss over each one, tap-tap-tapping away like IKEA’s shapeless man. At the end of my manly strivings I was confronted by a small black plastic unknown quantity. I assumed it was for joining the shelves together and hammered it onto the back of the unit. But the thing had an altogether different purpose. It was in fact meant to guide the nail as it’s being gingerly tapped into place at just the right distance from the edge, so as not to make an unsightly puncture in the backboard. Its conspicuous misplacement signaled my having failed at the masculine competency that can deduce a thing’s function simply from its design.

This little plastic doodad mocked me. It was strangely fitting that a lightweight piece of plastic had the heft to rattle the able-bodied do-it-yourself competency propping up my masculine self-concept. Confronted and confounded by my internal resistance to the IKEA imperative—its inane proceduralism and its mandated twosomeness—I suddenly became curious about how it is that I’ve come to identify so strongly with handyman competency. And I started to wonder about the history of how this gendered discourse has materialized in men’s bodies.

In his article “Do-It-Yourself: Constructing, Repairing and Maintaining Domestic Masculinity” Steven Gelber locates the introduction of ‘Mr. Fixit’ in America as early as 1870. The phenomenon was as gradual as the transition from “the distant Victorian father to the engaged and present suburban dad.” This restructuring of the American modern family had as much to do with property ownership, size, and location as it did with the changes wrought by industrialized and white-collar work, which stripped men of the practice of completing a task from start to finish with one’s own hands. What Gelber calls ‘domestic masculinity’, then, is an important counterpart to Margaret Marsh’s ‘masculine domesticity’. While the latter describes men’s gradual taking on of household tasks previously gendered feminine, the former is the exclusive staking out of a male sphere within the home in effort to reclaim an “aura of pre-industrial vocational masculinity” through such practices as woodworking, landscaping and handyman repair.

With the widespread suburbanization of the 1950s, domestic masculinity became firmly lodged within the gendered mindset of many American men. Even though IKEA began to spread into continental Europe, Australia and Canada in the 1970s, there were more than a few reasons they held off opening their first US store until 1985. In order for it to succeed as a multinational corporation, IKEA’s distinctly Swedish style of management needed to adopt a cross-cultural management style to suit each country. Comparing the US and Sweden on the Hofstede scale, Swedish culture has a lower power-distance index, is less ‘masculine’ and individualistic and more collective, non-hierarchically oriented. So not only did IKEA have to adjust to a different mindset with respect to corporate culture and workplace values, they also had to contend with America’s firmly rooted domestic masculinity.

At the risk of oversimplifying, we may observe that the complementary tension between Marsh’s masculine domesticity and Gleber’s domestic masculinity directly correlates with the competition between IKEA and D-I-Y outlets like Home Depot. Again, America’s suburbanization and history of home ownership differentiates it from many other countries in this respect. As a 2011 Forbes article notes, IKEA vastly outperforms Home Depot in China largely because home ownership there is really just beginning; as such, it has no pre-established D-I-Y culture.

But it is precisely this tension between masculine domesticity and domestic masculinity that intrigues me. It feels good to fix things; it’s true. It feels good to complete a task with your hands from start to finish. And though it seems this satisfaction springs from a particularly ‘masculine’ sensibility, I don’t think the feeling is exclusive to men. Even so, my resistance to IKEA’s tact-and-twosome approach to home furnishing clearly exposed my need to ‘stake my claim’ in the domestic sphere. I noticed how this need for gendered differentiation also seemed to demand a palpable hardening of my embodied presence. I’d venture to say it’s this same hard-bodied recalcitrance that creeps up in many of the men being towed along by their spouses through IKEA’s endless aisles. We needn’t look any further for proof of this tension than IKEA’s newly conceived ‘Manland’—much like its Småland, but outfitted for grown ups. Complete with videogames and foosball tables, men can conveniently evade IKEA’s eroding effects by retreating to their proverbial last stand: the ‘mancave’ entertainment zone.

As feminist history continues to expand, augment and intertwine with the way men and women speak and embody their gendered behaviors and practices, IKEA will continue to serve its inestimable role as the multinational flat pack & particle-board purveyor of masculine domestication. Though it needn’t be to the detriment of domestic masculinity, IKEA certainly works to help men be mindful of any of their hard edges standing at odds with so-called ‘domestic’ or ‘feminized’ ways of doing things. For me, IKEA requires patience, breathing, and good deal of humor to diffuse an inherited pattern that inevitably bubbles up. Having accomplished this feat—three PAX wardrobe units, a bed and a few nightstands—I can attest that my partner and I pulled it off without devolving into indignant hollering, which seemed less a triumph for her than me. There are, to be sure, at least two ways of doing things around the house, and a new set of challenges and pleasures afforded by embracing an IKEA masculinity.

But in fact I did have a female partner to help me, and in fact I did follow the instructions to the letter—because I’ve disobeyed the IKEA imperative before and the botched result made me feel even less manly than the kind of man IKEA would have me be. So it was absolutely necessary to obey the manual step-by-step, as a twosome, lifting together and sorting together, discussing, consulting, agreeing and building—with each of us up in each other’s business. It suddenly struck me that IKEA manuals aren’t instructions at all: they’re relationship and gender maps.

This realization came to me when I decided to deviate from our agreed-upon way of doing things and proceeded to hammer the backboard onto a wardrobe unit. Here I could finally reclaim some trace of manhood through the grip of a 12-pound hammer and a two-penny nail. I was determined to hammer each nail like a samurai, sinking each with a single strike. I’d be damned if I was going to fuss over each one, tap-tap-tapping away like IKEA’s shapeless man. At the end of my manly strivings I was confronted by a small black plastic unknown quantity. I assumed it was for joining the shelves together and hammered it onto the back of the unit. But the thing had an altogether different purpose. It was in fact meant to guide the nail as it’s being gingerly tapped into place at just the right distance from the edge, so as not to make an unsightly puncture in the backboard. Its conspicuous misplacement signaled my having failed at the masculine competency that can deduce a thing’s function simply from its design.

This little plastic doodad mocked me. It was strangely fitting that a lightweight piece of plastic had the heft to rattle the able-bodied do-it-yourself competency propping up my masculine self-concept. Confronted and confounded by my internal resistance to the IKEA imperative—its inane proceduralism and its mandated twosomeness—I suddenly became curious about how it is that I’ve come to identify so strongly with handyman competency. And I started to wonder about the history of how this gendered discourse has materialized in men’s bodies.

In his article “Do-It-Yourself: Constructing, Repairing and Maintaining Domestic Masculinity” Steven Gelber locates the introduction of ‘Mr. Fixit’ in America as early as 1870. The phenomenon was as gradual as the transition from “the distant Victorian father to the engaged and present suburban dad.” This restructuring of the American modern family had as much to do with property ownership, size, and location as it did with the changes wrought by industrialized and white-collar work, which stripped men of the practice of completing a task from start to finish with one’s own hands. What Gelber calls ‘domestic masculinity’, then, is an important counterpart to Margaret Marsh’s ‘masculine domesticity’. While the latter describes men’s gradual taking on of household tasks previously gendered feminine, the former is the exclusive staking out of a male sphere within the home in effort to reclaim an “aura of pre-industrial vocational masculinity” through such practices as woodworking, landscaping and handyman repair.

With the widespread suburbanization of the 1950s, domestic masculinity became firmly lodged within the gendered mindset of many American men. Even though IKEA began to spread into continental Europe, Australia and Canada in the 1970s, there were more than a few reasons they held off opening their first US store until 1985. In order for it to succeed as a multinational corporation, IKEA’s distinctly Swedish style of management needed to adopt a cross-cultural management style to suit each country. Comparing the US and Sweden on the Hofstede scale, Swedish culture has a lower power-distance index, is less ‘masculine’ and individualistic and more collective, non-hierarchically oriented. So not only did IKEA have to adjust to a different mindset with respect to corporate culture and workplace values, they also had to contend with America’s firmly rooted domestic masculinity.

At the risk of oversimplifying, we may observe that the complementary tension between Marsh’s masculine domesticity and Gleber’s domestic masculinity directly correlates with the competition between IKEA and D-I-Y outlets like Home Depot. Again, America’s suburbanization and history of home ownership differentiates it from many other countries in this respect. As a 2011 Forbes article notes, IKEA vastly outperforms Home Depot in China largely because home ownership there is really just beginning; as such, it has no pre-established D-I-Y culture.

But it is precisely this tension between masculine domesticity and domestic masculinity that intrigues me. It feels good to fix things; it’s true. It feels good to complete a task with your hands from start to finish. And though it seems this satisfaction springs from a particularly ‘masculine’ sensibility, I don’t think the feeling is exclusive to men. Even so, my resistance to IKEA’s tact-and-twosome approach to home furnishing clearly exposed my need to ‘stake my claim’ in the domestic sphere. I noticed how this need for gendered differentiation also seemed to demand a palpable hardening of my embodied presence. I’d venture to say it’s this same hard-bodied recalcitrance that creeps up in many of the men being towed along by their spouses through IKEA’s endless aisles. We needn’t look any further for proof of this tension than IKEA’s newly conceived ‘Manland’—much like its Småland, but outfitted for grown ups. Complete with videogames and foosball tables, men can conveniently evade IKEA’s eroding effects by retreating to their proverbial last stand: the ‘mancave’ entertainment zone.

As feminist history continues to expand, augment and intertwine with the way men and women speak and embody their gendered behaviors and practices, IKEA will continue to serve its inestimable role as the multinational flat pack & particle-board purveyor of masculine domestication. Though it needn’t be to the detriment of domestic masculinity, IKEA certainly works to help men be mindful of any of their hard edges standing at odds with so-called ‘domestic’ or ‘feminized’ ways of doing things. For me, IKEA requires patience, breathing, and good deal of humor to diffuse an inherited pattern that inevitably bubbles up. Having accomplished this feat—three PAX wardrobe units, a bed and a few nightstands—I can attest that my partner and I pulled it off without devolving into indignant hollering, which seemed less a triumph for her than me. There are, to be sure, at least two ways of doing things around the house, and a new set of challenges and pleasures afforded by embracing an IKEA masculinity.

Images: Ikea Catalog, http://www.mikesacks.com/ikea-instructions/

Originally published at The Good Men Project (26/12/13) and Masculinites 101 (12/2/13).

Originally published at The Good Men Project (26/12/13) and Masculinites 101 (12/2/13).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed