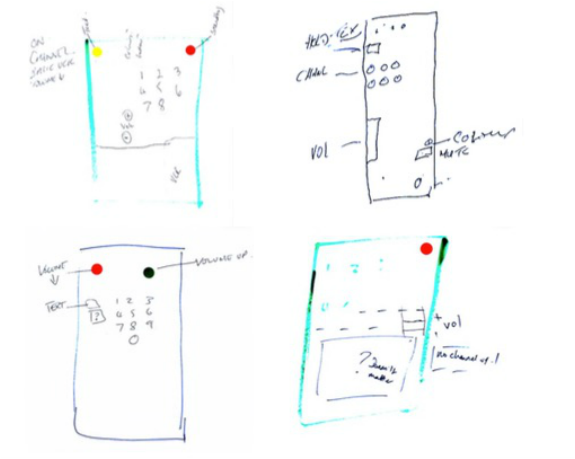

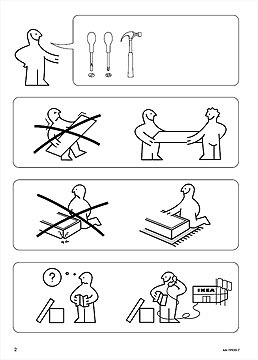

From a 2007 remote control usability study by Goldsmiths. Users were asked to sketch their remote controls from memory.

At the Society for Cinema and Media Studies this year in Atlanta, GA, I am excited to join David Parisi, Megan Sapnar Ankerson, and Carlin Wing as we tell design history tales about peripheral components in our home media networks. Come see us 12:15–2:00pm, Friday.

A brief description of our approach as outlined in the panel abstract:

"As links that interface between things, peripherals demonstrate the home media network as an assemblage of industrial negotiation. As ergonomically-crafted, material devices, they elucidate the embodied aspects of media interactivity. As objects within domestic space, their different uses underscore rich and multivalent life histories. By extending the boundaries of the machine through their contact with materiality, Lucy Suchman & Chris Chesher observe that peripherals play a crucial role in effecting the “managed indeterminacy” of the network. Centering on the peripheral as a historiographic tool offers a concrete strategy for understanding the material-discursive network that attends, shapes, and is co-shaped by changing habits and practices of home media consumption."

We are pleased to be sponsored by the Media, Science & Technology Scholarly Interest Group.

Panel Summary

Title: Centering on the Peripheral: Design Histories of Home Media Networks

Panel number: L19 | Friday, 2:15-2pm

Chair: Brent Strang • Stony Brook University

David Parisi • College of Charleston

"Designing, Domesticating, and Disputing Gamic Touch: The Case of the Rumble Apparatus"

Brent Strang • Stony Brook University

"Armchair Harmonics: Designing Logitech's Harmony One Remote Control"

Megan Sapnar Ankerson • University of Michigan

"From Desktop Publishing to Everyday iLife: Configuring Peripherals in the Digital Home"

Carlin Wing • New York University

"Made for TV: The Mediatic Life of the Optic Yellow Tennis Ball"

Presentation Abstracts

Designing, Domesticating, and Disputing Gamic Touch: The Case of the Rumble Apparatus

The 1997 release of Sony’s DualShock controller for its first-generation PlayStation console saw the migration of vibration feedback technology (or ‘rumble’) from the arcade into the living room, via the controller-as-peripheral. The DualShock’s rumble apparatus--two spinning motors housed in the controller’s handles--produced a complex array of haptic effects, purportedly adding to the sense of realism in game worlds. With Microsoft adopting a similar mechanism for its XBox console in 2001, rumble seemed poised to remain a constant in future generations of videogame consoles.

However, in 2002 the diminutive technology firm Immersion Corporation claimed that the dual-motor feedback mechanism infringed on two patents it owned, and filed lawsuits against both Sony and Microsoft. While Microsoft quickly settled the suit, Sony began what would prove to be a protracted courtroom battle with Immersion. By 2005, an injunction against Sony prevented it from selling DualShock controllers in the US. The company announced it would not feature rumble in its forthcoming console, which sparked a public feud between the companies’ CEOs. Sony’s Phil Harrison indicated that the company had made a crucial design choice to go with motion control instead of rumble, asserting that rumble would interfere with the accuracy of the controller’s motion sensing mechanism. Immersion’s Vic Viegas fired back, offering to solve the problem through their expertise in “filtering techniques, processing techniques, and through hardware modifications.” When released in November, rumble remained missing from the PS3. In the interim, Immersion commissioned a market research survey showing gamers had a strong preference for the absent feature. With the PS3’s sales figures lagging behind the XBox 360, Sony announced a settlement with Immersion in 2007. As a result, it released a new PS3 controller with both rumble and motion control, restoring gamic touch to the PlayStation console, and calling into question Harrison’s claim about the mutual exclusivity of the two features.

Through an examination of the political theater surrounding the rumble apparatus’ legal contestation , this paper shows how the design, diffusion, and iterative refinement of gamic touch was underpinned by agitations from a variety of contextually-situated actors: engineers, lawyers, consumers, market researchers, game journalists, and corporate executives each figured into the process of rumble’s gradual domestication.

Armchair Harmonics: Designing Logitech's Harmony One Remote Control

In her book Beyond the Multiplex, Barbara Klinger stresses how different venues of spectatorship shape content reception. However, her analyses of contemporary home theaters are limited to how marketing and decorative appeal establish class-conscious constructions of value and taste. Beyond the scope of its spectacularization, the home theater milieu is also exhaustively designed to respond to, facilitate, and further incline embodied habits and practices in ways users scarcely notice. As an everyday object within this milieu, the remote control device (RCD)—with its contoured shape, sensuous feel, and interaction design—bears traces of a nexus of historical forces, including the patterns of exhibition and distribution, the network of connected components, and the state of the language of tactile interactivity.

In 2006, the same year Klinger’s book was published, Logitech began working on what may well be the most intensively researched and developed universal remote control in history. With 20,000 hours in development, around $15,000,000 in R&D costs, and 2,000 customers providing feedback and hands-on testing in Logitech’ s laboratory, the Harmony One staked its claim in the living room as the “mouse of the digital house.” I analyze Logitech’s corporate archives and interviews with their employees and outsourced contractors through a design history heuristic. Mapping the network of actors involved details the extensive debate leading to the Harmony’s final iteration. For example, industrial designers and ergonomists wanted to remove button-clutter and ease the thumb’s abduction, while users insisted that certain buttons, such as the PVR menu and numeric keypad, had to remain tactile and not moved to the LCD screen.

After the Harmony One’s enormous initial success, advanced universal remotes suffered a steep decline in worldwide sales. With the increased prevalence of low-cost cell phone apps, smart TV, and voice control, we might assume that the Harmony One reached the high-water mark, and that hard-buttoned, handheld RCDs will soon be a thing of the past. On the contrary, the reams of data that Logitech collected from usability testing attest to users' sophisticated opinions on how to improve RCD interaction design, and their deep emotional preferences for physical, hand-held tokens of access and control. Design history methods can thus shed light on how technological advances remain in dialectical tension with users' entrenched habits and practices.

From Desktop Publishing to Everyday iLife: Configuring Peripherals in the Digital Home

In 1985, the “desktop publishing revolution” captivated the personal computer industry with promises of typeset-quality documents produced with inexpensive, small, user-friendly equipment that was easy to maintain and seamlessly connected. The suite of tools that comprised desktop publishing—Apple Macintosh, Aldus’s PageMaker layout software, Apple’s LaserWriter printer, and Adobe’s PostScript page description language that handled communication between devices—was hailed for democratizing the publishing process by bringing “professional-grade” production to mass market. While democratization of publishing discourses have long been linked to small press movements, mimeograph and zine culture, less attention has been paid to historicizing how values and devices are reconfigured alongside domestic everyday life and broader socio-technical changes in mediated environments.

This paper approaches peripherals as a historiographical toolset for analyzing the shifting relations between objects, industries, practices, and meanings that inform the design of everyday digital life. What happens, in other words, when we follow the material-semiotic trail of desktop publishing from 1985 into the 21st century digital home, where mac minis function as home media servers, Google ChromeCast brings internet streaming to TV, and Apple’s iLife suite of creativity apps serves as the hub for a “digital lifestyle” that links music, video, and photography to home printers, TVs, and stereos? As the terms “desktop” and “publishing” are mobilized to signal new ways of organizing, editing, creating, and sharing media, they take on specific cultural meanings underpinned by the design of new technical processes (i.e., synching devices across the cloud)

and shifting industrial alliances (i.e., the fallout between Apple and Adobe). Analyzing a collection of marketing materials and design specs from the Computer History Museum archives, I draw on Lucy Suchman’ s notion of “configuration” as a type of method assemblage for probing how artifacts and imaginaries are entangled together and reconfigured over time. I focus on three moments of transition: desktop publishing in mid-80s, web publishing in mid-90s, and the bundling of creativity apps (Apple’s iLife) in mid-2000s. I propose “peripheral relationality” can help us do media studies in ways that foreground connection and change while remaining attuned to historical context, industrial negotiations, and media convergence.

Made for TV: The Mediatic Life of the Optic Yellow Tennis Ball

This paper considers the lives and afterlives of the officially sanctioned tennis ball. In 1972—the era of Billie Jean King and Arthur Ashe—the International Tennis Federation (ITF) introduced a rare change into the rules of tennis. To account for research that demonstrated that yellow balls were more visible to television viewers, the balls, which had previously been covered with white felt, would now be made with yellow felt. Tennis balls were already industrially produced, precisely pressurized, pneumatic objects: made to mediate surfaces in a reliable manner. They were designed for the kind of true bounce that allowed players to hit a “good ball.” This color change acknowledged that the ball was now accountable to a new surface, the television screen, and to a new set of eyes, the audience. The ball now needed to behave properly both physically and optically. In 2014, the ITF introduced another rare rule change: "smart" equipment (equipment that reports real-time biostatistics, feedback on ball force, impact position, etc.) would be allowed during competition. This created another loop into mediatic life for both ball and player. Sony promises that when your racket takes on the role of a camera and your phone takes on the role of a television, you, the player, will be able to “turn your game on.”

Although tennis balls are now “made for TV,” their moment in the sun is short-lived. They begin to lose pressure the minute they leave their cans. In fact, the vast majority of balls never pass in front of a camera’s lens or encounter a racket’s sensor, instead filling hoppers and ball machines around the world. Nevertheless, their “made for TV” aesthetic has lodged itself firmly in our domestic landscapes. They lie at the bottom of sports closets and beach bags; buffer the metal ends of senior citizens’ walkers and gaffers’ film rigs; and are joyfully chewed by dogs everywhere. Drawing on historical research, materials from the ITF, as well as research trips to the USTA technical committee meeting and the USTA ball testing facility, I consider the material, color, pressure, and other specifications that underpin the ball’s performance, and, picking up Langdon Winner’s question “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” together with Raiford Guins’s call for us to attend to the afterlives of game materials, I follow the trajectory of the ball as it passes through its moment of high performance potential and sensor scrutiny, before rolling off to rest under the couch.

A brief description of our approach as outlined in the panel abstract:

"As links that interface between things, peripherals demonstrate the home media network as an assemblage of industrial negotiation. As ergonomically-crafted, material devices, they elucidate the embodied aspects of media interactivity. As objects within domestic space, their different uses underscore rich and multivalent life histories. By extending the boundaries of the machine through their contact with materiality, Lucy Suchman & Chris Chesher observe that peripherals play a crucial role in effecting the “managed indeterminacy” of the network. Centering on the peripheral as a historiographic tool offers a concrete strategy for understanding the material-discursive network that attends, shapes, and is co-shaped by changing habits and practices of home media consumption."

We are pleased to be sponsored by the Media, Science & Technology Scholarly Interest Group.

Panel Summary

Title: Centering on the Peripheral: Design Histories of Home Media Networks

Panel number: L19 | Friday, 2:15-2pm

Chair: Brent Strang • Stony Brook University

David Parisi • College of Charleston

"Designing, Domesticating, and Disputing Gamic Touch: The Case of the Rumble Apparatus"

Brent Strang • Stony Brook University

"Armchair Harmonics: Designing Logitech's Harmony One Remote Control"

Megan Sapnar Ankerson • University of Michigan

"From Desktop Publishing to Everyday iLife: Configuring Peripherals in the Digital Home"

Carlin Wing • New York University

"Made for TV: The Mediatic Life of the Optic Yellow Tennis Ball"

Presentation Abstracts

Designing, Domesticating, and Disputing Gamic Touch: The Case of the Rumble Apparatus

The 1997 release of Sony’s DualShock controller for its first-generation PlayStation console saw the migration of vibration feedback technology (or ‘rumble’) from the arcade into the living room, via the controller-as-peripheral. The DualShock’s rumble apparatus--two spinning motors housed in the controller’s handles--produced a complex array of haptic effects, purportedly adding to the sense of realism in game worlds. With Microsoft adopting a similar mechanism for its XBox console in 2001, rumble seemed poised to remain a constant in future generations of videogame consoles.

However, in 2002 the diminutive technology firm Immersion Corporation claimed that the dual-motor feedback mechanism infringed on two patents it owned, and filed lawsuits against both Sony and Microsoft. While Microsoft quickly settled the suit, Sony began what would prove to be a protracted courtroom battle with Immersion. By 2005, an injunction against Sony prevented it from selling DualShock controllers in the US. The company announced it would not feature rumble in its forthcoming console, which sparked a public feud between the companies’ CEOs. Sony’s Phil Harrison indicated that the company had made a crucial design choice to go with motion control instead of rumble, asserting that rumble would interfere with the accuracy of the controller’s motion sensing mechanism. Immersion’s Vic Viegas fired back, offering to solve the problem through their expertise in “filtering techniques, processing techniques, and through hardware modifications.” When released in November, rumble remained missing from the PS3. In the interim, Immersion commissioned a market research survey showing gamers had a strong preference for the absent feature. With the PS3’s sales figures lagging behind the XBox 360, Sony announced a settlement with Immersion in 2007. As a result, it released a new PS3 controller with both rumble and motion control, restoring gamic touch to the PlayStation console, and calling into question Harrison’s claim about the mutual exclusivity of the two features.

Through an examination of the political theater surrounding the rumble apparatus’ legal contestation , this paper shows how the design, diffusion, and iterative refinement of gamic touch was underpinned by agitations from a variety of contextually-situated actors: engineers, lawyers, consumers, market researchers, game journalists, and corporate executives each figured into the process of rumble’s gradual domestication.

Armchair Harmonics: Designing Logitech's Harmony One Remote Control

In her book Beyond the Multiplex, Barbara Klinger stresses how different venues of spectatorship shape content reception. However, her analyses of contemporary home theaters are limited to how marketing and decorative appeal establish class-conscious constructions of value and taste. Beyond the scope of its spectacularization, the home theater milieu is also exhaustively designed to respond to, facilitate, and further incline embodied habits and practices in ways users scarcely notice. As an everyday object within this milieu, the remote control device (RCD)—with its contoured shape, sensuous feel, and interaction design—bears traces of a nexus of historical forces, including the patterns of exhibition and distribution, the network of connected components, and the state of the language of tactile interactivity.

In 2006, the same year Klinger’s book was published, Logitech began working on what may well be the most intensively researched and developed universal remote control in history. With 20,000 hours in development, around $15,000,000 in R&D costs, and 2,000 customers providing feedback and hands-on testing in Logitech’ s laboratory, the Harmony One staked its claim in the living room as the “mouse of the digital house.” I analyze Logitech’s corporate archives and interviews with their employees and outsourced contractors through a design history heuristic. Mapping the network of actors involved details the extensive debate leading to the Harmony’s final iteration. For example, industrial designers and ergonomists wanted to remove button-clutter and ease the thumb’s abduction, while users insisted that certain buttons, such as the PVR menu and numeric keypad, had to remain tactile and not moved to the LCD screen.

After the Harmony One’s enormous initial success, advanced universal remotes suffered a steep decline in worldwide sales. With the increased prevalence of low-cost cell phone apps, smart TV, and voice control, we might assume that the Harmony One reached the high-water mark, and that hard-buttoned, handheld RCDs will soon be a thing of the past. On the contrary, the reams of data that Logitech collected from usability testing attest to users' sophisticated opinions on how to improve RCD interaction design, and their deep emotional preferences for physical, hand-held tokens of access and control. Design history methods can thus shed light on how technological advances remain in dialectical tension with users' entrenched habits and practices.

From Desktop Publishing to Everyday iLife: Configuring Peripherals in the Digital Home

In 1985, the “desktop publishing revolution” captivated the personal computer industry with promises of typeset-quality documents produced with inexpensive, small, user-friendly equipment that was easy to maintain and seamlessly connected. The suite of tools that comprised desktop publishing—Apple Macintosh, Aldus’s PageMaker layout software, Apple’s LaserWriter printer, and Adobe’s PostScript page description language that handled communication between devices—was hailed for democratizing the publishing process by bringing “professional-grade” production to mass market. While democratization of publishing discourses have long been linked to small press movements, mimeograph and zine culture, less attention has been paid to historicizing how values and devices are reconfigured alongside domestic everyday life and broader socio-technical changes in mediated environments.

This paper approaches peripherals as a historiographical toolset for analyzing the shifting relations between objects, industries, practices, and meanings that inform the design of everyday digital life. What happens, in other words, when we follow the material-semiotic trail of desktop publishing from 1985 into the 21st century digital home, where mac minis function as home media servers, Google ChromeCast brings internet streaming to TV, and Apple’s iLife suite of creativity apps serves as the hub for a “digital lifestyle” that links music, video, and photography to home printers, TVs, and stereos? As the terms “desktop” and “publishing” are mobilized to signal new ways of organizing, editing, creating, and sharing media, they take on specific cultural meanings underpinned by the design of new technical processes (i.e., synching devices across the cloud)

and shifting industrial alliances (i.e., the fallout between Apple and Adobe). Analyzing a collection of marketing materials and design specs from the Computer History Museum archives, I draw on Lucy Suchman’ s notion of “configuration” as a type of method assemblage for probing how artifacts and imaginaries are entangled together and reconfigured over time. I focus on three moments of transition: desktop publishing in mid-80s, web publishing in mid-90s, and the bundling of creativity apps (Apple’s iLife) in mid-2000s. I propose “peripheral relationality” can help us do media studies in ways that foreground connection and change while remaining attuned to historical context, industrial negotiations, and media convergence.

Made for TV: The Mediatic Life of the Optic Yellow Tennis Ball

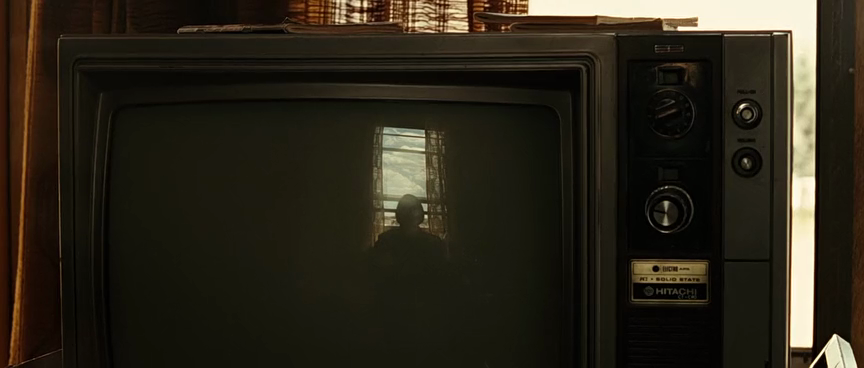

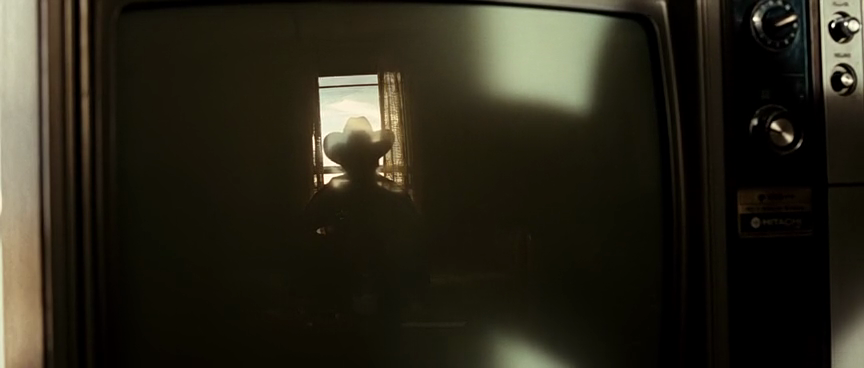

This paper considers the lives and afterlives of the officially sanctioned tennis ball. In 1972—the era of Billie Jean King and Arthur Ashe—the International Tennis Federation (ITF) introduced a rare change into the rules of tennis. To account for research that demonstrated that yellow balls were more visible to television viewers, the balls, which had previously been covered with white felt, would now be made with yellow felt. Tennis balls were already industrially produced, precisely pressurized, pneumatic objects: made to mediate surfaces in a reliable manner. They were designed for the kind of true bounce that allowed players to hit a “good ball.” This color change acknowledged that the ball was now accountable to a new surface, the television screen, and to a new set of eyes, the audience. The ball now needed to behave properly both physically and optically. In 2014, the ITF introduced another rare rule change: "smart" equipment (equipment that reports real-time biostatistics, feedback on ball force, impact position, etc.) would be allowed during competition. This created another loop into mediatic life for both ball and player. Sony promises that when your racket takes on the role of a camera and your phone takes on the role of a television, you, the player, will be able to “turn your game on.”

Although tennis balls are now “made for TV,” their moment in the sun is short-lived. They begin to lose pressure the minute they leave their cans. In fact, the vast majority of balls never pass in front of a camera’s lens or encounter a racket’s sensor, instead filling hoppers and ball machines around the world. Nevertheless, their “made for TV” aesthetic has lodged itself firmly in our domestic landscapes. They lie at the bottom of sports closets and beach bags; buffer the metal ends of senior citizens’ walkers and gaffers’ film rigs; and are joyfully chewed by dogs everywhere. Drawing on historical research, materials from the ITF, as well as research trips to the USTA technical committee meeting and the USTA ball testing facility, I consider the material, color, pressure, and other specifications that underpin the ball’s performance, and, picking up Langdon Winner’s question “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” together with Raiford Guins’s call for us to attend to the afterlives of game materials, I follow the trajectory of the ball as it passes through its moment of high performance potential and sensor scrutiny, before rolling off to rest under the couch.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed